Since 2007, poaching of wildlife and in particular the poaching of White Rhinos, Black Rhinos and African Elephants, has been at the forefront of the conservation battle in southern Africa. The combination of increasing demand for rhino horn and ivory as well as high black market prices in Asian markets (especially Vietnam and China) has fuelled increase in poaching (Ferreira et al. 2014).

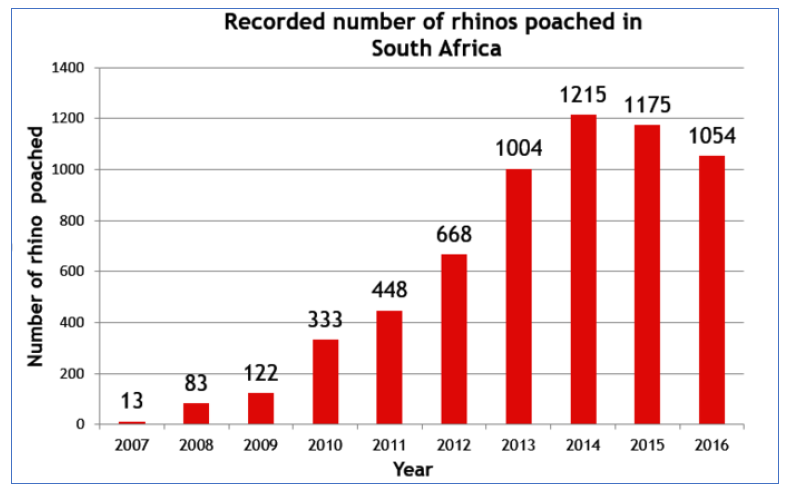

South Africa has by far the largest population of rhinos in the world and is an incredibly important country for rhino conservation. From 2007–2014 South Africa experienced an exponential rise in rhino poaching — a growth of over 9,000%!

Rhino horn has been used in traditional Asian medicine as a perceived cure for everything from cancer to hangovers, however the recent spike in demand has been driven by an increasing desire for rhino horn as a status symbol in Vietnam. Global education campaigns by WildAid in both China and Vietnam have been used in an attempt to educate those purchasing rhino horn and reduce demand. However the illegal trade in rhino horn continues to persist.

In South Africa, around a quarter of the total population of rhino are found on private land. The owners of these reserves and game farms are increasingly hiring specialized companies that focus on the protection of wildlife and the apprehension of poachers

Most illegal activity occurs in the Kruger National Park (KNP), which is 19,485 km2 (almost 2 million hectares) in size and lies on South Africa’s north-eastern border with Mozambique (Ferreira et al. 2014). The Kruger National Park consistently suffered heavy poaching loses, and so in the last few years the South African government and international donors have channelled ever more funding and resources into securing the Park.

© Kirstin Scholtz

The Kruger National Park is divided into three zones in terms of rhino concentration: The far north has the smallest population, which makes up approximately 26% of the total, south of the Olifants River. The majority of the rhino population is concentrated in the southern part of the Park. Sadly, since elephant poaching has started to escalate in the northern part of the Park, in addition to the rhino crisis in the southern part, the rangers are facing a huge challenge as response times to poaching incidents are critical.

Poaching methods

Snares

The snares are mainly made of wire and tied to branches. A loop of the wire is positioned in such a way that if the animal walks on the game path, it will get its head caught in the loop, which tightens as it is pulled. The poacher sets snares at different levels and sizes depending on the animal’s size and species which he wishes to catch. However, when the snare is old or has fallen to the ground, it remains in the game path and can snare anything from a small steenbok to an animal as large as a giraffe. Predators such as lions, hyenas and leopards also get caught in snares.

Poaching with dogs

This form of poaching is a successful method, and very difficult to monitor. Those very experienced poachers tend to make use of the full moon to infiltrate farms whilst hunting with dogs. The poachers’ dogs are very well trained, moving silently and obediently through the bush. Poachers often walk with two sticks, tapping them in various ways to give orders to the dogs. The game caught is mainly warthogs. The poachers often build fires in the entrance to the warthog holes to smoke the animals out and then the dogs are trained to bring the warthog to the ground. During winter, the dogs are also used to chase bigger game (such as kudu, wildebeest, zebra) until exhaustion sets in. The game is weaker during this time because of the poor nutrient quality of the grass.

Military style poaching of rhinos/elephants

In recent decades, the poaching of rhinos and elephants has been executed with almost military style precision. Poachers are armed and dangerous and animals are usually killed with a gun or rifle, the horn or ivory is cut off, and it is rare that any other body parts are taken.

Although the majority of poaching occurs during the night, there are also incidents happening during the day. Despite specific tendencies regarding poaching, such as that it sometimes happens more frequently during weekends and during the full moon, poachers adapt when there are operations during full moon and then focus their poaching activities during dark moon phases. Poachers adapt easily to changing circumstances.

Skulls of poached rhinos

Current rhino poaching figures (Department of Environmental Affairs 2017)

In 2016, figures show a dip in poaching in South Africa for the second year in a row, indicating that increased protection efforts are paying off. Although it is encouraging to see South Africa’s poaching levels fall, the losses are still extremely high. A rise in incidents outside Kruger National Park also points to the growing sophistication of poaching gangs that are gaining a wider geographical coverage and, it would seem, expanding their operations across borders.

Rhino poaching was declared a National Priority Crime in 2014 and the issue continues to receive the highest level of attention from the Department of Environmental Affairs (DEA), the country’s law-enforcement authorities, and the prosecution service (Department of Environmental Affairs 2017).

A total of 414 alleged poachers have been arrested in South Africa since 1 January 2016 — of which 177 were in the KNP and 237 for the rest of the country. A total of 94 firearms have been seized inside the KNP between 1 January and 31 August 2016 (Department of Environmental Affairs 2017).

Between January and the end of August 2016, a total number of 458 poached rhino carcasses were found in the KNP, compared to 557 in the same period in 2015. This represents a 17.8% decline in the number of rhino carcasses.

Poaching rates, i.e. the number of carcasses as a percentage of the number of live rhinos estimated the previous September for each year, reduced by 15.5% compared between the same periods in 2015 (9.6% poaching rate) and 2016 (7.9% poaching rate).

These figures come amidst a 27.87 % increase in the number of illegal incursions into the KNP — a staggering 2115 illegal incursions for the first eight months of 2016.

Nationally, 702 rhino were poached since the beginning of 2016 whereas between January and July 2015, a total of 796 rhinos were poached. There may be indications however that the success of anti-poaching efforts in the KNP has led to poaching syndicates shifting operations to other provinces.

In the period under review, the number of rhino poached has increased in a number of other provinces in comparison to the same period in 2015, such as KwaZulu-Natal, Free State Province and the Northern Cape Province.

However, despite these increases there is still a downward trend in the number of rhino poached.

It is also of concern that we have begun experiencing an increase in elephant poaching, despite the vigorous and determined efforts by game rangers, the police and soldiers on the ground. Since January 2016, 36 elephants have been poached in the KNP.

The combined efforts of DEA, law-enforcement and the conservation agencies — with the support of international partners and donors, are slowly but steadily making a dent in the rhino poaching numbers.

Figure 1 Rhino poaching figures for 2007–2016 (Department of Environmental Affairs 2017)

Local communities must be involved in the fight against poaching

It has become clear throughout Africa and the rest of the world that in order for conservation efforts to succeed local communities living in or near protected areas must and should be involved in conservation management decisions. Local communities must benefit from conservation.

There is a passive involvement from the communities who are staying or operating in the surrounding areas of the Kruger, since they will often not report poachers to the authorities. The reason for this is that the money that is derived from poaching plays a vital role in the poor communities. The fact that the KNP does not really add value to the communities also plays a big role in their passivity — having a vast piece of land which is used for nature conservation neither benefits nor makes sense to them.

A Committee of Inquiry (CoI) as appointed by the Minister of Environmental Affairs presented a report on rhino poaching at the 2016 CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) COP17 conference

The CoI agreed there was an urgent need to improve both socio-economic conditions of rural communities neighbouring protected areas and their relationships with agencies managing protected areas, to develop a conducive environment for strong mutual partnerships around natural resource management and beneficiation.

The CoI suggested the following minimum requirements to effectively address community empowerment:

- Functional municipalities around key protected areas to provide water, waste, sanitation, energy, roads, transport, education and health services through joint engagement by communities and conservation agencies with all relevant government departments;

- A Champion to be appointed to oversee Community Empowerment, in a permanent position with multi-departmental influence and funding, to develop and implement a Community Empowerment plan addressing these requirements which acknowledges past errors associated with protected area policies;

- Increased access to education and capacity building opportunities in these communities, specifically through a targeted Mentorship Programme to provide qualifications and develop advanced skills in conservation and protected area management for community members and entry into protected area management opportunities;

In order to create real opportunities for local communities in the conservation and wildlife management space, and thus ensuring that they are less vulnerable to exploitation by poachers, the following steps need to be taken (and in some cases already are) (Department of Environmental Affairs 2013):

- Develop a reward or incentives system that supports the development of small businesses in communities to discourage them from becoming involved in poaching

- Capacity building within communities

- Identify and implement suitable community wildlife management projects

- Raise funding for the implementation of community-based programmes;

- Identify and support legitimate Rhino awareness campaigns

Anti-poaching methods

There is probably no single piece of technology that will be a game changer, but every item forms part of the solution. Rangers on the ground are still the most effective anti-poaching method, but what about the following:

Rangers training at the South African Wildlife College

Is rhino dehorning effective?

Rhino dehorning has been used historically as a tool to reduce the threat of poaching in parts of southern Africa, and continues to be employed on a large-scale in Zimbabwe. Dehorning is contentious due to uncertainty regarding the effectiveness of the method at reducing poaching, and due to potential veterinary impacts and adverse effects on the behavioural ecology of rhinos.

Historical and current use of dehorning (Endangered Wildlife Trust 2012)

- Rhino dehorning was first practiced in Namibia, in Damaraland and part of Etosha National Park, and was undertaken in the country from 1989 until 1995.

- In South Africa, dehorning appears to be practiced to an increasing extent in the private sector, and has been undertaken in provincial parks in Mpumalanga Province and in Rietvlei Dam Nature Reserve in Gauteng.

- Dehorning is not undertaken in the South African National Parks (SANParks, which includes Kruger) or in any other provincial reserves in South Africa.

The positives of dehorning (Endangered Wildlife Trust 2012)

- In Mpumalanga, tentative insights from the dehorning programme in the provincial parks suggest that dehorning has caused a reduction in poaching losses.

- Mpumalanga has 1,071 rhinos (excluding those in Kruger) of which 347 have been dehorned. Mpumalanga province started dehorning in August 2010, though several private owners started well before then. In 2009, 2010 and 2011 (up to the end of August) 6, 17 and 10 rhinos were poached respectively, of which one was dehorned.

- In the Hoedspruit area, following the widespread dehorning of rhinos in mid- 2011, information was received by private landowners that a poaching group had decided to focus efforts on other areas where rhinos still retained their horns. However, rhino owners in that area acknowledge that it is too early to assess the efficacy of the dehorning programme.

- Most (71.7%) experts felt that dehorning can be an effective means of dissuading poachers from targeting a particular reserve, but 52.6% felt that once a poacher was in a reserve, he would be no less likely to shoot a dehorned rhino if such an animal was encountered, than a horned individual.

The negatives of dehorning (Endangered Wildlife Trust 2012)

- In Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe, dehorning of White Rhinos in the early 1990s failed to protect them (as the majority of horned and dehorned rhinos were killed by poachers) due to a complete lapse in security for a period of six months 12–18 months after the rhinos were dehorned.

- In South Africa, at least five incidents have been recorded of dehorned rhinos being killed by poachers since 2008. In one incident, a horned rhino was wounded by poachers, and then dehorned by management and placed in a boma, where poachers returned to kill the animal despite clearly being able to see that the animal was dehorned (F. Coetzee, pers. comm.).

- These experiences clearly highlight that dehorning in the absence of intensive security is likely to be ineffective, and stresses that horn stumps are still valuable to poachers.

- Dehorning partially transfers the risk of horn possession from rhinos to the land manager, and creates administrative burdens and costs through the time and effort needed to acquire permits, transport and storage of horns.

- The permitting system for possessing, transporting and storing horn is considered by private rhino owners to be onerous and to impose security risks by providing a conduit for leakage of information on the whereabouts of horns or on planned transportation of horns.

© Shannon Wild

The effectiveness of remotely piloted aircraft systems in the fight against poaching

A study by Mulero-Pazmany et al. (2014) assessed the use of remotely piloted aircraft systems (RPAS) to monitor for poaching activities. They performed 20 flights with 3 types of cameras: visual photo, HD video and thermal video, to test the ability of the systems to detect (a) rhinos, (b) people acting as poachers and © to do fence surveillance. The targets were better detected at the lowest altitudes, but to operate the plane safely and in a discreet way, altitudes between 100 and 180 m were the most convenient. Open areas facilitated target detection, while forest habitats complicated it. Detectability using visual cameras was higher at morning and midday, but the thermal camera provided the best images in the morning and at night. Considering not only the technical capabilities of the systems but also the poachers’ modus operandi and the current control methods, Mulero-Pazmany et al. (2014) proposed RPAS usage as a tool for surveillance of sensitive areas, for supporting field anti-poaching operations, as a deterrent tool for poachers and as a complementary method for rhino ecology research.

Low cost RPAS can be useful for rhino stakeholders for field control procedures. There are, however, important practical limitations that should be considered for their successful and realistic integration in the anti-poaching battle.

Anti-poaching Units

The game rangers and anti-poaching units that patrol the Greater Kruger area spend most of their time out in the field, in harm’s way and away from home and their families. Their families do not always know when they will get to see them again. The rangers’ stress levels are high and, as one can imagine, it is not always easy for their families.

Anti-poaching units in the Hoedspruit area

The Black Mambas

The Black Mambas are all-women anti-poaching unit. They are all young women from local communities, and they patrol inside the Greater Kruger national park unarmed. Billed as the first all-female unit of its kind in the world, they are not just challenging poachers, but the status quo. The Black Mamba anti-poaching unit is a great example of utilising people from the local communities, getting them involved in conservation, providing them with employment, and upliftment.

The Black Mamba anti-poaching unit was founded in 2013 by Transfrontier Africa and created to protect the Olifants West Region of Balule Nature Reserve and has since expanded to cover the entire Balule area, 400km².

The private reserve’s scientists and managers have had to become warriors, employing teams of game guards to protect not only the rhinos but lions, giraffes, and many other species targeted by poaching syndicates. The Mambas are the reserve’s eyes and ears on the ground.

The anti-poaching statistics for the area suggest the Black Mamba approach works. During the last 10 months of 2014 and the start of 2015 the Balule Nature Reserve had not lost a single rhino, while a neighbouring reserve lost 23. Snare poaching has also by dropped 90%.

ProTrack Anti-Poaching Unit

Protrack Anti-Poaching Unit was established in 1992 as one of the first private anti-poaching units in South Africa. They provide anti-poaching training and recruitment in the Hoedspruit area. They also provide specialist rural security services to farms and nature reserves.

Rhino Revolution

Rhino Revolution was started by the concerned citizens of Hoedspruit, including conservationists and private nature reserve owners, who came together to try and reduce the escalating poaching crisis in this critically important rhino conservation area. They started as a community based action group, under the auspices of founder Trevor Jordan. Rhino Revolution is now an internationally recognised Non-Profit Organization. Rhino Revolution supports rhino conservation through rigorous anti-poaching activities, conservation awareness programmes and the provision of a world class rhino orphanage (situated within the Blue Canyon Conservancy, with electric fencing, lighting, intruder alarm systems and watch towers with 24 hour armed guards.).

Rhino Revolution’s anti-poaching efforts:

- Rhino Revolution has provided night vision equipment for Hoedspruit Farm Watch, provided a new anti-poaching vehicle for the Blue Canyon Anti-Poaching Unit together with radios, weapons and ammunition and, installed solar power at the Essem Scout Camp.

- Rhino Revolution also funds dehorning of rhino.

- Rhino Revolution uses retired racehorses for anti-poaching patrols, as the mounted guards can reach areas inaccessible to vehicles, quickly and silently, and efficiently look out for any signs of criminal intent from the elevated field of vision that horseback patrols offer.

Key factors in rhino security

The following components are essential for effective anti-poaching security for rhinos (Endangered Wildlife Trust 2012):

Undertake a thorough threat analysis of property:

- Evaluate all possible threats (e.g. know the most likely entry and exit points, know the locations of rhinos [see field monitoring below]).

- Prepare response plans for as many eventualities as possible.

Secure the property:

- Electrified fencing that is monitored and maintained.

- Control entry points onto property with guarded boom gates.

Field protection:

- Rangers must be well trained in weapons, anti-poaching tactics and drills. Rangers must be well equipped, with: assault rifles (AK47 or equivalent) Handheld radios, spare batteries

- Backpacks, water bottles, rations

- Maps, GPS devices, binoculars

- Rangers must be authorised and empowered to aggressively respond to and engage poachers when necessary and have indemnity against legal proceedings in the same way that police do.

- Rangers should be adequately paid and rewarded to maintain motivation (and avoid collusion with poachers). But, the reward system must be sustainable.

- Ranger density should be: minimum of 1 ranger for every 20 km2 but under conditions of high poaching threat: 1 ranger for every 10 km2 is recommended. In large reserves: concentrate Rangers where rhinos occur. In large reserves (>200 km2) there should be a mobile anti-poaching reaction unit with rapid deployment capabilities — set up in picket camps situated in peripheral high risk areas. There should be routine patrols around fences and buffer zones for the early detection of poacher incursions, as well as at sites where poachers will focus attention (e.g. water points, vantage points good for surveillance).

- Field monitoring: auxiliary staff well trained in tracking and identifying rhinos (to allow rapid detection of poaching) should be deployed. Monitoring of rhinos should proceed with the use of standardised field recording booklets and a density of at least 1 ranger per 20 rhinos

- Rhinos should be ear-notched to facilitate individual identification and to provide accurate and unbiased population estimates of population performance

Rhino in the afternoon light © Kirstin Scholtz

Check out WildArk’s recent visit to the South African Wildlife College where the unit revealed their skill in sniffing out rhino horn as well as apprehending a ‘poacher’ in Mick Fanning who dressed in a protection suit before being tackled by one of the trained dogs.

Some further reading:

References:

Department of Environmental Affairs. 2017. Progress highlights in the fight against rhino poaching. Available at: www.environment.gov.za.

Department of Environmental Affairs. 2013. Rhino dialogues introduction. Available at: www.environment.gov.za

Emslie R. 2012. Ceratotherium simum, Diceros bicornis IUCN Red List Threat Species Version 2012. Available: www.iucnredlist.org.

Endangered Wildlife Trust. 2012. Research report: A study on the dehorning of the African rhinoceroses as a tool to reduce the risk of poaching. On behalf of the Department of Environmental Affairs, South Africa.

Ferreira SM, Pfab M and Knight M. 2014. Management strategies to curb rhino poaching: Alternative options using a cost–benefit approach. South African Journal of Science 110 (5/6).

Geldenhuys K. 2016. Rhino poaching in the Kruger National Park. Servamus Community-based Safety and Security Magazine, Volume 109: 10–17.

Knight M. 2011. African Rhino Specialist group report. Pachyderm: 6–15.

Mulero-Pa´zma´ny M, Stolper R, van Essen LD, Negro JJ and Sassen T. 2014. Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems as a Rhinoceros Anti-Poaching Tool in Africa. PLoS ONE 9(1): e83873. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0083873