Dr Julian and Stephanie Fenessy with their two kids at home in Namiba. © Fennessy, GCF

When you think of Africa, the long-necked, gentle giraffe is probably not far from your mind. While they may seem plentiful, giraffe are facing an uncertain future with a 40% decline in the last 30 years. They are now listed as vulnerable.

In light of the threat to one of Africa’s most charismatic species, Dr. Julian and Stephanie Fennessy of the Giraffe Conservation Foundation have dedicated their lives to ensuring the survival of the world’s tallest animal.

Collectively they are renowned as the world’s leading giraffe experts and Co-Founders of the Giraffe Conservation Foundation which they run from their home in Windhoek, Namibia. Julian is Co-Chair and Stephanie, Secretary of the IUCN SSC Giraffe & Okapi Specialist Group which they also helped establish. They have spent the past 20 years researching and working with others to protect giraffe populations across Africa.

“People think giraffe are everywhere, but the reality is they are on a path towards a silent extinction,” says Julian.

Angolan giraffe herd in Damaraland, NW Namibia © Fennessy, GCF

Threats range from habitat destruction to poaching, but there are even more sinister reasons why giraffe are disappearing at a rapid rate.

“In Tanzania, we have some reports that people think the bone marrow is a cure for HIV Aids,” says Stephanie. “In the DRC, the tail is very popular, and we have found two giraffe carcasses with just their tail cut off. What a waste!”

“If you’re caught with ivory or with elephant meat, there are high fines. Whereas giraffe are easy to hunt, there’s a lot of meat, and they’re just not as highly protected.”

Julian’s experience in the field of giraffe conservation means he knows giraffe better than anyone. With a background in species and habitat ecology, conservation and land management across Africa and Australia, Julian also boasts experience in individual field projects, supervision of students, population and country-wide assessments and he continues to advise governments on the development of national giraffe conservation strategies and action plans. He has also conducted numerous conservation expeditions across every region of the Africa continent.

The couple met while working together in Namibia 1999, and were married in 2003 before moving back to Australia for a few years. In 2010 Julian and Stephanie, along with their two kids, moved back to Windhoek permanently. They have spent over 20 years researching the Angolan Giraffe in the desert of far northwestern Namibia, establishing the Giraffe Conservation Foundation to raise funds and support increased education and awareness worldwide.

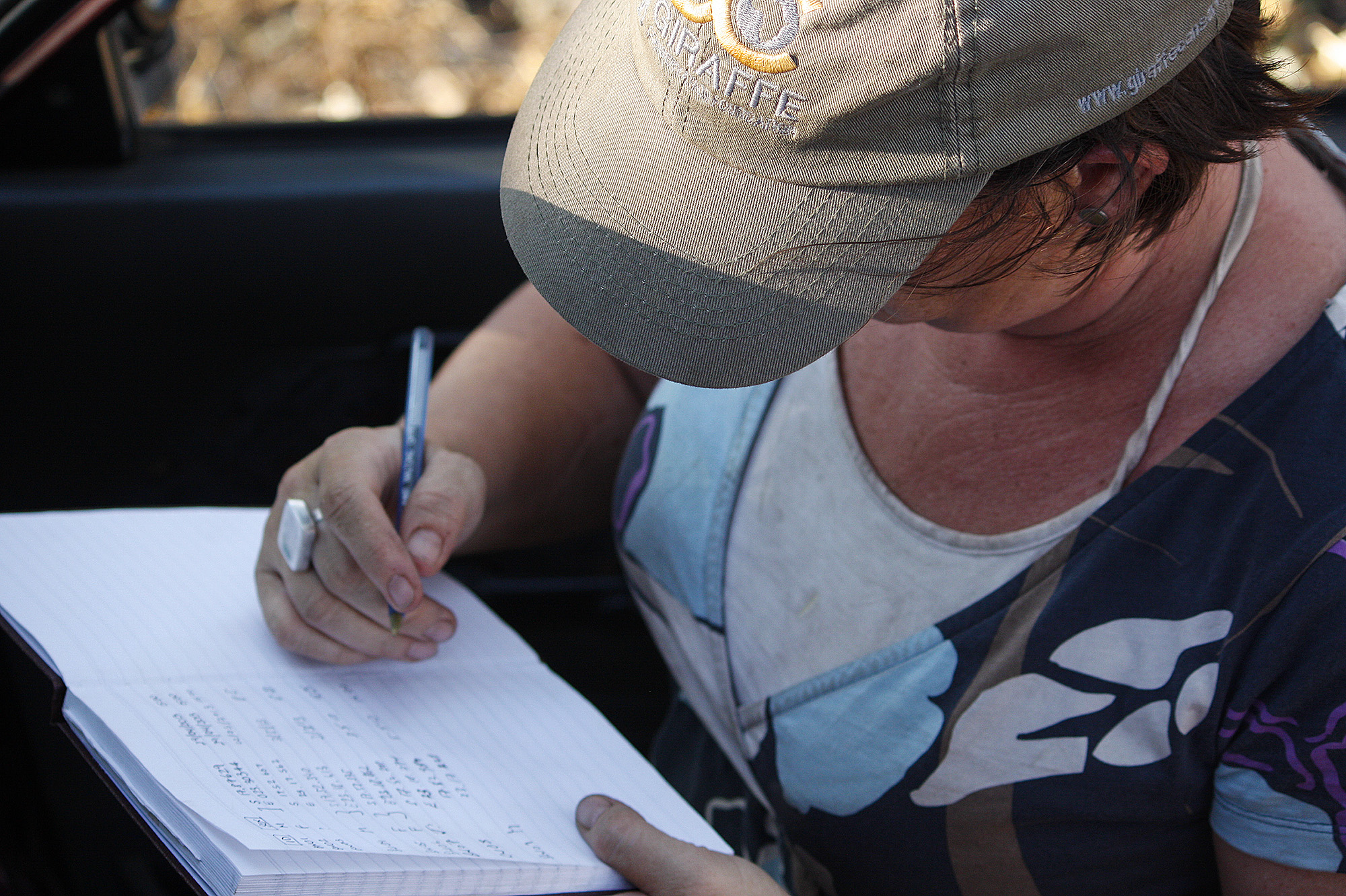

Nubian giraffe collaring in Ethiopia © Fennessy, GCF and (Right) Stephanie Fennessy working on data collection © Fennessy, GCF

Stephanie’s work extends beyond the day-to-day business of GCF, specialising in project management within the private, Government and NGO sector on three continents — Africa, Australia and Europe. Her expertise ranges from community-based natural resource management to technical sustainability solutions.

While she particularly enjoys the fieldwork component, she is quick to point out that researching giraffes is not as exciting as one may think.

“It’s pretty boring actually,” says Stephanie. “We did a lot of ‘activity budgets’ where we would sit in the car for up to 10 hours a day and watch one giraffe, and write down what it did every minute for ten hours! And as it turns out, they don’t do much!”

Working in one of the world’s harshest desert climates is where Julian feels most at home. Researching giraffe movement in and around the far northwestern Namibia, a landscape that receives less than 100mm of rain per year, has given him unique insight into the survival of this species.

“There’s a fog that comes in from the coast and influences the way certain wildlife survive there,” says Julian. “In the first five years, I never saw a giraffe drink, which I thought was maybe me being a bit stupid. What I later realised was that this fog that comes in from the coast, on an average of 250 days a year, is absorbed by trees and the giraffes absorb a lot more moisture by eating from these trees during the early morning hours. They don’t need to drink. It all comes down to survival, and that is obviously one of the best ways that they have been able to survive.”

Giraffe collaring © Fennessy, GCF

Julian and Stephanie established the first use of GPS satellite collars for giraffes in the early 2000’s, contributing to exponential learning on giraffe movements. Their findings offered insight into the best ways to protect giraffe and provided specific details into the landscapes in which they thrive.

Perhaps the couple’s most significant contribution, however, has been their research into species DNA. For nearly 20 years, they have been working to figure out ‘who is who in the giraffe zoo’. By working with people across the continent, they have been collecting giraffe DNA samples to understand the different species of giraffe and how much hybridisation there is between species.

“We have about a million and a half years of separation between some of these giraffe species. If we took that in the context of bears — there are brown bears and polar bears, and they’re about 800,000 years in separation — so the whole theory of what a species is, has been thrown out of the window over the years.”

Masai giraffe © Billy Dodson

Northern Giraffe © Fennessy, GCF

Southern Giraffe © Fennessy, GCF

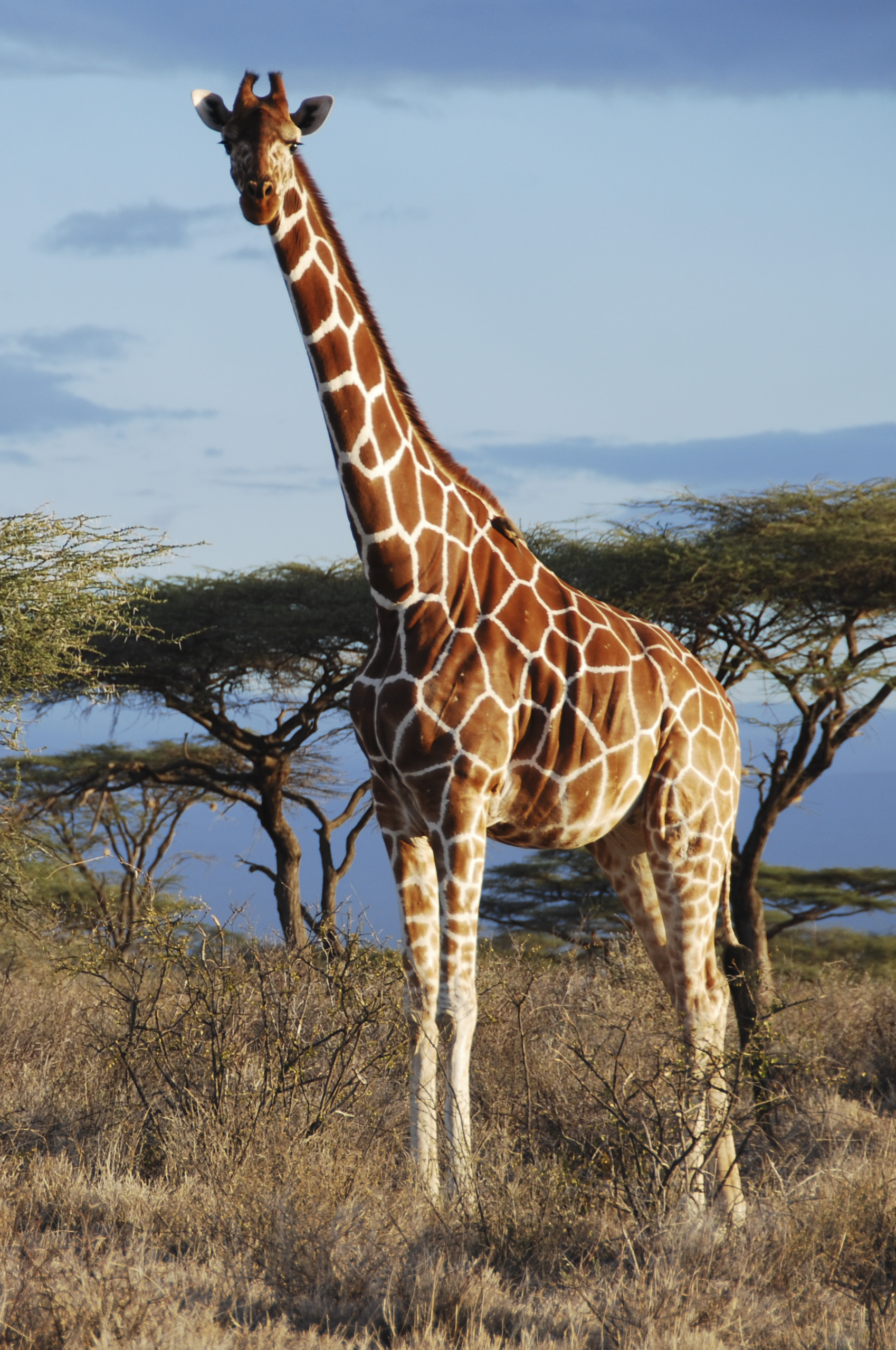

Reticulated Giraffe © Fennessy, GCF

What Julian hopes to demonstrate is that perhaps we shouldn’t move giraffe around if they are different species. It might be important not to mix Masai Giraffe, with Reticulated Giraffe, for example.

The most interesting research has come out of Kenya, where the couple has been working with the Kenyan Wildlife Service to collect DNA samples. Kenya is home to three species of giraffe and is a hotspot for the giraffe. With nearly 300 samples taken to date, the team will begin analysing the data.

“We know giraffe breed together in zoos, but why don’t they do it in the wild?” says Julian. “Thats the big question and the reason, from all our samples so far, is that they just don’t, and there has to be a good ecological factor that we don’t yet understand.”

But it’s not all data and science for the Fennessys whose work can be as diverse as sitting in front of a computer working on budgets, to planning a translocation, writing a giraffe strategy for a country or translocating a giraffe across the Nile River.

“We’ve done two big translocations in Uganda in the past two years,” says Stephanie. “It is physical work bringing a giraffe to the ground safely. We worked with a fantastic team from the Ugandan Wildlife Authority and spent a few tough and dangerous days translocating giraffe. There was lots of excitement and exhilaration, particularly at the end when you see giraffe crossing the Nile on a little ferry, and then you release them on the other side.”

In a daring mission to secure the future of Nubian giraffe, the Giraffe Conservation Foundation partnered with the Uganda Wildlife Authority in Murchison Falls NP, Uganda. Twiga is the Swahili word for ‘giraffe’.

For Julian, the design improvements in giraffe tagging units have brought him great personal satisfaction in improving the welfare of these animals.

“Whenever we bring down an animal it’s scary. You have to give a massive drug overdose to bring down a giraffe, and every time it gets back up — that’s the most amazing feeling!”

Partnerships with governments are essential for the Giraffe Conservation Foundation whose model is to supply all giraffe conservation support. They work with many African governments, including their most successful, working with the Ugandan Government in developing a national strategy for giraffe conservation.

“Unless you have government buy-in and support, everything will be just interim, so developing national strategies and working closely with governments is critical,” says Julian.

“We don’t want to grow to be a huge organization, where we are in different countries with different projects. We think it’s a much better strategy for us to support others to do work in an area they know. We are strategic in picking partners. We work a lot with governments; we work with local and national NGO’s. We look to find the best partners in every set up where we think it’s important to work.”

(Top) Giraffe await their departure for Uganda in the safety of a boma. © Fennessy, GCF; (Bottom) Transporting giraffe across the Nile river to their new home in Uganda. © Fennessy, GCF

In addition to their work on the ground, the Fennessys have been instrumental in raising awareness for giraffe conservation worldwide by establishing World Giraffe Day (21 June — the longest day or night for the tallest animal) to raise awareness and funds for their tall friends.

Embraced by zoos around the world, Giraffe Conservation Foundation works with many of these organisations for mutual benefit.

“We work with zoos by getting keepers out into the field, to increase their passion and make them ambassadors for giraffe and GCF,” says Stephanie.

“In Uganda, we had a group of American vets with us as well as other giraffe experts who were involved with the capture, and they helped us look after the giraffe when they were in the boma because that is their expertise.”

Giraffe collaring © Fennessy, GCF

With the help of the specialists, the first ever x-rays of giraffe hooves were performed in the wild, thanks to the Giraffe Conservation Foundation. With a variety of issues with hoof health affecting giraffe in captivity, the x-rays gave insight into the difference in feet between wild and zoo giraffe, so that zoos can better care for the animals they have there.

In chatting to the Fennessys, it soon becomes evident that they turned their passion into their day job, however the work they are doing remains the former.

With a schedule that takes Julian from Namibia to Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda, Paris and USA in the first six months of 2018, there’s no doubt about his commitment to the giraffe.

“I feel like I have grown up with these animals, they are my mates. Everyone thinks giraffe are everywhere but their numbers are plummeting, and I think it would be a sorrowful world without giraffe,” says Julian.

Stephanie is equally dedicated.

“They are amazing animals, when you see them out in the wild they are pretty unique and iconic,” says Stephanie. “It feels like we are making a difference and not many people can say that.”

To support the wonderful work that Julian and Stephanie are doing visit the Giraffe Conservation Foundation website or make a donation.